The Tenth Man: Book Excerpt from Wei Wu Wei

THE TENTH MAN

19. Boomerang

I am confused….

About what?

The doctrine.

Inevitably: there isn’t any.

I mean about how things work….

They don’t.

Well, then, about how and what we are?

There can be no how or what: we aren’t.

Then I am and I am not….

I neither am nor am not.

You neither are nor are not?

I; you simply are not.

All right, then, this which I neither am nor am not, and that which you simply are not.

What is there left to be confused about?

So that is it?

There is no ‘it’.

Then what is the use of words?

They are perfect.

As what?

A boomerang.

20. Bewildering Bits and Painful Pieces – 1.

Light does not find the Darkness of a ‘me’ because the Darkness of a ‘me’ was never anything but the absence of the Light.

* * *

We are miserable unless the sun is shining, but if the sun were shining within we should not even notice whether the feeble phenomenal sun was shining or not.

* * *

It needs supreme humility in order to understand, and absolute silence of mind. It might even be said that absolute humility IS understanding. Why? What does ‘humility’ signify except absence of consciousness of self?

* * *

‘You have no need to seek deliverance, since you are not bound’.

Hui Hai speaking.

* * *

Turn the light on to yourself – and, believe me, you’ll find nothing there.

* * *

Fear, desire, affectivity are manifestations of the pseudo-entity which constitutes pseudo-bondage.

It is the entity, rather than the manifestations thereof, which has to be eliminated.

* * *

‘I’ is a part, but I am the whole.

* * *

However fast you run after it, you will never catch it; however fast you run away from it, you will never lose it.

There is no ‘I’ because there is no other-than-I.

* * *

I cannot become what I am.

An eye sees, but does not look.

I look.

* * *

The Individual As He Is

There is no other self to know the self of an individual self than the self which he is.

(Since the ‘individual’ is inseparable from what-he-is, like flame and fire, there is no self to know the individual except the self which is inseparable from what-he-is.)

(Paraphrase of Maharshi from ‘Self Enquiry’)

* * *

The quality called ‘humility’ refers to the lack of anyone to possess it.

* * *

‘You cannot see it because you are transparent.’

(stop reading until you see what this means).

* * *

I am the awareness of being aware that I am universal awareness, the first dim, the second brilliant, the last a blinding radiance.

* * *

Beware of beatified individuality.

* * * *

THE TENTH MAN

PART II : SELF AND OTHER

Every sentient being, speaking as I, may say to his phenomenal self,

‘Be still! and know that I am God!’

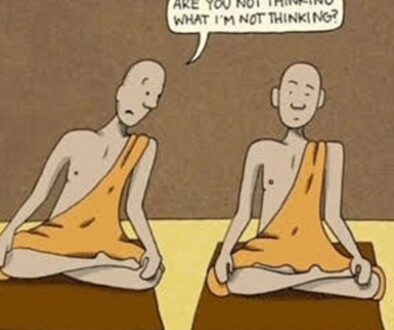

21 : The Big Joke

I

As long as there is a ‘you’ doing or not-doing anything, thinking or not-thinking, ‘meditating’ or ‘not-meditating’, you are no nearer home than the day you were ‘born’.

However many years you may have been at it, and whatever you have understood or have not-understood, you have not yet started if there is a ‘you’ that is still in the saddle.

As long as you do anything as from a ‘you’, you are in ‘bondage’.

Here the word you stands for any object that appears to act or not to act, that is any phenomenon as such. ‘You’ stands for any such object which believes that it acts volitionally as an autonomous entity, and is thereby bound by identification with a phenomenon.

Let us say it again: as long as there is a pseudo-entity apparently doing or not-doing anything, thinking or not-thinking, meditating or not-meditating, that phenomenon is no nearer home than the day it was apparently born.

However many years a phenomenon may have been at it, and whatever it has understood or not-understood, it has not yet started if there is a pseudo-entity that is still in the saddle.

As long as a phenomenon does anything as from a pseudo-entity, it is in ‘bondage’.

The difference is between what you are and what you think you are but are not, ‘bondage’ being identification of the former with the latter.

Again: the difference is between This which every phenomenon is and That which no phenomenon is, ‘bondage’ being identification of the former with the latter.

That, in very simple language, is the pseudo-mystery, the so-called insoluble problem, the joke that made Lazarus Laugh.

II

Treating this matter in the first person singular, it becomes a question of what we mean when we say ‘I’.

If in saying ‘I’ we speak as from a psycho-somatic phenomenon that believes itself to be an independent entity acting or not-acting autonomously as a result of its own volition, then no matter what we may know or ignore, what we may have practised or not-practised, we are well and truly in bondage.

If in saying ‘I’ – although we may speak as from a phenomenon that appears to act or not to act (as observed by other phenomena and by ‘itself’) – we do not regard that phenomenon as possessing of its own right and nature any autonomy or volition, and so is properly to be regarded not as ‘I’ but as ‘it’, then since such phenomenon is not ‘in the saddle’ I am not identified with it, and I am not in bondage.

In this latter case the word ‘I’ is subjective only, as the word ‘Je’ in French, and for the accusative (or objective) case the word ‘me’ is necessary, as is ‘moi’ in French, even after the verb ‘to be’, for ‘I’ have no objective quality whatever, and all that could be called ‘me’ can never in any circumstances have any subjective quality, so that what I am as ‘I’ is purely noumenal and what I appear to be as ‘me’ is exclusively phenomenal. So that in saying ‘I’, if we speak or act as from what we are – from impersonal noumenality, with the spontaneity that is called ‘Tao’, there is no longer any question of bondage, for there is no longer any supposed entity to be bound.

III

There is a further stage of fulfillment, in which complete reintegration takes place. Therein ‘I’ and ‘it’, ‘I’ and ‘you’, subject and object, lose all elements of difference. Of this stage only the fully integrated can be qualified to speak with authority, for herein no differentiation any longer is possible.

I am you, you are I, subject is object, and object is subject, each is either and either is both, for phenomena are noumenon and noumenon is phenomena.

This is the end of the big joke, the final peal of laughter, for it, too, is so simple and obvious that only the blindfold should fail to see it, or could see it in any other manner.

Said as we say it, however that may be, it can never be true; said as the integrated say it, however that may be – even in the self-same words – it cannot be false: for what is neither false nor true cannot be false as it cannot be true. It is what it is – and whatever it be called, that it can never be.

22. Prajna

When contact is made, by means of a switch, the electric current flows, the wire is instantly ‘alive’, the resistance becomes white-hot, and there is light.

When contact is broken, the current no longer passes, the resistance cools, there is darkness, and the line is ‘dead’.

The electric current is what is implied by ‘prajna‘ where sentient beings are concerned: it is the act of action, the living of life.

Nobody knows what electricity is, nobody knows what prajna is: both terms are just names given to concepts that seek to describe in dualistic language a basic ‘energy’ that enables appearance to appear and being to be.

When contact is made we know it as ‘light’ and as ‘life’; when contact is broken we know it as ‘darkness’ and ‘death’. But the source of ‘energy’ remains intact and intangible.

Are we the hot resistance and the light, the cold resistance and the darkness – or the vital current itself?

23. The Loud Laugh

Is it not all a great joke – which has been made a mystification by the devotionally-minded, no doubt because the suffering consequent on identification with a pseudo-entity (which so deeply impressed the Buddha), invites compassion (affectivity)?

But it is the huge joke that we should see, and loud laughter that should greet the seeing, for it is the simplicity and the obviousness of it, in contrast with the monumental superstructure of superfluous mystification that has been built round it, that calls forth the laughter.

The Ch’an Masters saw this, and said it? Saw it they certainly did, but they rarely did more than imply it. They were monks in monasteries and had their own particular conditioning. But whenever the sudden seeing of it was greeted with laughter by the see-er – the Master joined in the jest.

In a sense all Ch’an practice tends towards this irreverent revelation, for devotion is limitation, and so a binding, like any other. A superficial scaffolding of religiosity was maintained by these outwardly pious Buddhists, but the essential irreverence of their teaching, of their wen-ta (Jap. mondo), was the method by which they taught.

This is still the case today as regards the devotional background, but the reverential element has re-established itself at the expense of the straight-seeing, and to just that degree Ch’an has lost its efficacy and its appeal.

Philosophy can only reach it when the limit of rationality (dialectics) is reached, and the philosopher allows himself to pass over into pure metaphysics.

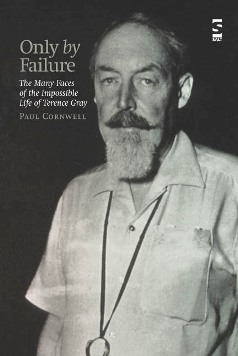

Terence James Stannus Gray, better known by the pen name

Wei Wu Wei, was a 20th-century Taoist philosopher and writer.

Born: September 14, 1895, Suffolk, United Kingdom

Between the years 1958 and 1974 eight books and articles in various periodicals appeared under the pseudonym “Wei Wu Wei” (Wu wei, a Taoist term which translates as “action that is non-action”). The identity of the author was not revealed at the time of publication for reasons outlined in the Preface to the first book, Fingers Pointing Towards the Moon (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1958). Eventually it was revealed that the author had been Terence Gray.

Terence James Stannus Gray was born in Felixstowe, Suffolk, England on 14 September 1895, the son of Harold Stannus Gray and a member of a well-established Irish family. He was raised on an estate at the Gog-Magog Hills outside Cambridge, England. He received a thorough education at Ascham St Vincent’s School, Eastbourne, Eton and Oxford University. Early in life he pursued an interest in Egyptology which culminated in the publication of two books on ancient Egyptian history and culture in 1923. This was followed by a period of involvement in the arts in Britain in the 1920s and 1930s as a theorist, theatrical producer, creator of radical “dance-dramas”, publisher of several related magazines and author of two related books. He was a major influence on many noted dramatists, poets and dancers of the day, including his cousin Ninette de Valois, founder of the Royal Ballet (which in fact had its origins in his own dance troupe at the Cambridge Festival Theatre which he leased from 1926 to 1933).

He maintained his family’s racehorses in England and Ireland and in 1957 his horse Zarathrustra won the Ascot Gold Cup, ridden by renowned jockey Lester Piggott in the first of his eleven wins of that race.

After he had apparently exhausted his interest in the theatre, his thoughts turned towards philosophy and metaphysics. This led to a period of travel throughout Asia, including time spent at Sri Ramana Maharshi‘s ashram in Tiruvannamalai, India. In 1958, at the age of 63, he saw the first of the “Wei Wu Wei” titles published. The next 16 years saw the appearance of seven subsequent books, including his final work under the further pseudonym “O.O.O.” in 1974. During most of this later period he maintained a residence with his wife Natasha Imeretinsky in Monaco. He is believed to have known, among others, Lama Anagarika Govinda, Dr. Hubert Benoit, John Blofeld, Douglas Harding, Robert Linssen, Arthur Osborne, Robert Powell and Dr. D. T. Suzuki. He died in 1986 at the age of 90.

Wei Wu Wei’s influence, while never widespread, has been profound upon many of those who knew him personally, upon those with whom he corresponded, among them British mathematician and author G. Spencer-Brown and Galen Sharp, as well as upon many who have read his works, including Ramesh Balsekar.

Wei Wu Wei is published by Sentient Publications

http://www.sentientpublications.com/